Apr 03, 2017

Getting started with HTTP in Go

12 min read

I have been writing/learning Go for the past one month. It has been a pleasurable one month and has rekindled the joy i had when i wrote my Hello World program.

HTTP in all it's majesty is made up of requests and responses, no matter what it has been frankensteined to look like. And this is as true as that at Go's end.

In this post, i would be taking a dive into the standard net/http package in other to explain the process of handling requests and returning responses in Go.

This blog post is written for new Gophers.

Basics

In languages like PHP and Ruby, we have the concepts of

Routers := Receives the request, then dispatch accordingly.

Controllers := Handles the dispatched HTTP request. A controller can either be an object or a closure.

What about Go ?

In Go, we have only Handlers. Seriously. There aren't routers. Everything is an Handler. And this is only possible because Go is a very opinionated language. Standards are first citizens here.

So how does Request dispatching and Response transfer work

I talked about standards the other time, all Handlers must implement a certain interface from the net/http standard library

type Handler interface {

ServeHTTP(ResponseWriter, *Request)

}Starting with responses, HTTP in Go relies on the interface described above

All handlers (take that as controllers for a second) MUST have that signature, i.e a ServeHTTP method that must be called to handle the dispatched request.

ResponseWriter;s job is to write the header, data bytes while the Request helps in inspecting the HTTP request.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

// associate URLs requested to functions that handle requests

http.Handle("/hello/lanre", &HelloWorld{"Lanre"})

http.Handle("/hello/doe", &HelloWorld{"John doe"})

http.HandleFunc("/", getRequest)

// start web server

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":9999", nil))

}

type HelloWorld struct {

Name string

}

func (h *HelloWorld) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprint(w, "Hello "+h.Name)

}Don't worry about the code. The only thing of interest right now is we have a struct (object ?) called HelloWorld that has a

ServeHTTPmethod which handles both routes (which makes it a controller).

Visiting localhost:9999/hello/lanre should spit "Hello Lanre" while localhost:9999/hello/doe should give use "Hello John doe".

What about Routers ? What dispatches the request to a controller ?

Routers in Go are called Multiplexers or ServeMuxes.

But regardless of all the overloaded names, they are nothing more than regular handlers.

A router is an handler in the fact that it also satisfy the http.Handler interface. That is they have a ServeHTTP method.

The only difference between a handler and other handlers - middleware, controllers - is that this handler is some sort of a root handler.

As a root handler, you get to attach other handlers to it.

Then when it gets run i.e the ServeHTTP method is called, it then dispatches the request to a registered handler (controller/middleware) interested in the route.

This even makes the idea of tinkering with a custom made router cool.

Go's philosophy is batteries included hence the standard library comes with a router that can be utilized in any application.

In fact, we already made use of it in the code block above http.Handle.

func main() {

http.Handle("/hello/lanre", &HelloWorld{"Lanre"})

http.Handle("/hello/doe", &HelloWorld{"John doe"})

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":9999", nil))

}The http package comes with the Handle and HandleFunc functions (which we used above) that helps map routes to handlers.

func Handle(pattern string, handler Handler) { DefaultServeMux.Handle(pattern, handler) }

func HandleFunc(pattern string, handler func(ResponseWriter, *Request)) {

DefaultServeMux.HandleFunc(pattern, handler)

}The DefaultServeMux

As you can see from the code block above, the package level functions - Handle and HandleFunc - are actually syntactic sugar for attaching routes to

a ServeMux - one provided by net/http. They actually defer to DefaultServeMux.Handle.

It is starting to get a bit fuzzy and it seems like there is lot of autowiring here <sup>0</sup>.

type ServeMux struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

m map[string]muxEntry

hosts bool // whether any patterns contain hostnames

}

type muxEntry struct {

explicit bool

h Handler

pattern string

}

func NewServeMux() *ServeMux { return new(ServeMux) }

var defaultServeMux ServeMux

var DefaultServeMux = &defaultServeMuxSample app

Basically, what Go does is instantiate a ServeMux for you. var DefaultServeMux = &defaultServeMux.

Without this, http.Handle wouldn't work since we do not have an instance of DefaultServeMux.

Let's have a look at a simple but contrived example in other to put together the pieces we have seen so far - handlers (controllers) and errm, handlers (router). I like ancient mythology of gods (Greek and Egyptian), so we would be building something of that sort.

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

type user struct {

ID int `json:"id"`

Moniker string `json:"moniker"`

Bio string `json:"bio"`

Languages []string `json:"languages`

}

var allUsers []*user

func init() {

allUsers = []*user{

{ID: 1, Moniker: "Hades", Bio: `god of the underworld, ruler of the dead

and brother to the supreme ruler of the gods, Zeus`, Languages: []string{"Greek"}},

{ID: 2, Moniker: "Horus", Bio: `god of the sun, sky and war`, Languages: []string{"Arabic"}},

{ID: 3, Moniker: "Apollo", Bio: `god of light, music, manly beauty, dance, prophecy, medicine,

poetry and almost every other thing. Son of Zeus`, Languages: []string{"Greek"}},

{ID: 4, Moniker: "Artemis", Bio: `goddess of the wilderness and wild animals.

Sister to Apollo and daughter of Zeus`, Languages: []string{"Greek"}},

}

}

func main() {

http.Handle("/users/", users{})

http.ListenAndServe(":4000", nil)

}

type users struct {

}

func (u users) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

j, _ := json.Marshal(allUsers)

fmt.Fprintf(w, string(j))

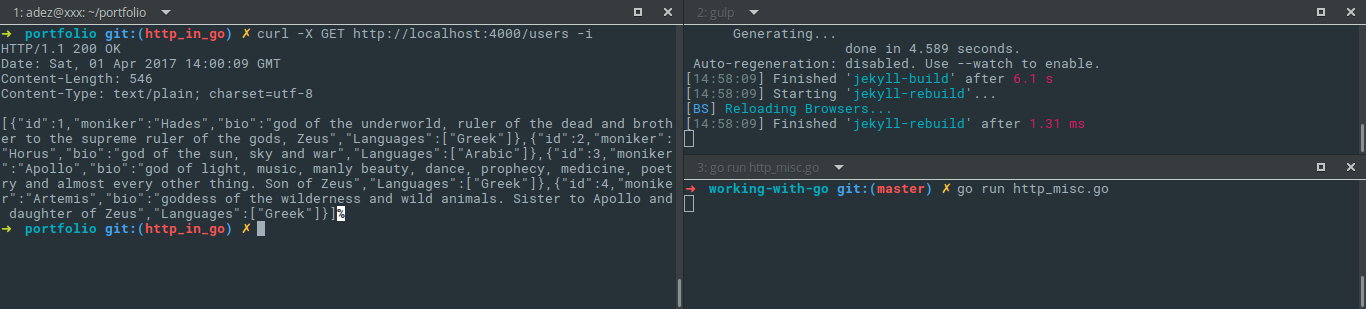

}You should open up a console

go run http_test.go #if the above was saved as http_test.goAfter which you make a request to localhost:4000, i prefer to use curl.

Since we have go running our app already, we need another console window - I use a tiling terminal (guake mode in Tilix)

The top left window is what you are looking for

While this is powerful enough to help build web applications, there are issues with the DefaultServeMux

that must be considered before taking it into production (which our startup sadly enough has done).

This considerations have nothing to do with performance but usabilty. While i list them as drawbacks, there are workarounds for them and i show the process of removing this drawbacks.

- For every new route, a complementary

structmust be created. This can get pretty frustating and tiring.

The only exception here is when we decide to reuse the same struct in multiple routes as we did with the

HelloWorldstruct.

The workaround :

Use functions

http.HandleFunc("/about", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

fmt.Fprintf(w, "You just reached the page of our startup. Thank you for visiting")

})That doesn't compile right ? Handlers are supposed to have a ServeHTTP method.

Well yes, but the Go team helped with a little bit of abstraction.

Go has a HandlerFunc type that has the same signature as the ServeHTTP method.

Due to Go's flexibility, types can have methods - even if the type is a string.

With this in mind, the HandlerFunc adapts itself with a ServeHTTP method in which it just cleverly calls itself i.e the function you passed in.

type HandlerFunc func(ResponseWriter, *Request)

// ServeHTTP calls f(w, r).

func (f HandlerFunc) ServeHTTP(w ResponseWriter, r *Request) {

f(w, r)

}Basically, the HandleFunc method just adapts a function into a http.Handler interface

// HandleFunc registers the handler function for the given pattern.

func (mux *ServeMux) HandleFunc(pattern string, handler func(ResponseWriter, *Request)) {

mux.Handle(pattern, HandlerFunc(handler))

}When you call HandleFunc, it justs adapts the function into a http.Handler.

- Lack of parametized routes (

/users/:id)

Let's assume we were in a rush to ship an MVP as soon as possible, then we shipped the above code as is.

The code runs fine after which you share the link of your new company on Twitter.

And all is fine for the next few minutes until someone - who likes mythology and knows REST- tries to get the details for a god with a specific id.

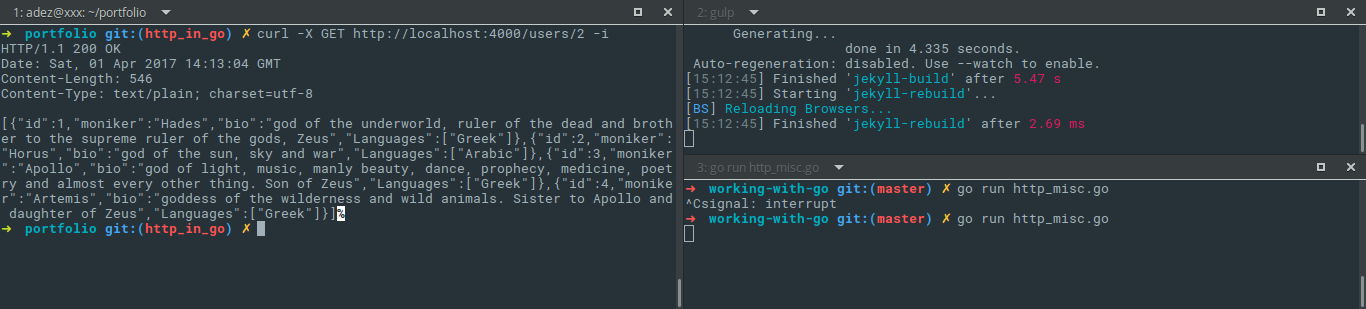

Remember our json response has an id field. He then sends an HTTP request to localhost:9999/users/2.

Whoops!!! Same response with the

/users/path and they aren't the same URL. Our startup has been broken.

This isn't a bug.

The DefaultServeMux provided by net/http doesn't try to solve all problems and this is quite understandable <sup>1</sup>. The way DefaultServeMux works is this :

Routes matching are very strict. Like very strict. It only checks if the request path has a prefix as that which was registered on the router, discarding the remainder path._

Here is the implementation of how paths are matched :

func pathMatch(pattern, path string) bool {

if len(pattern) == 0 {

// should not happen

return false

}

n := len(pattern)

if pattern[n-1] != '/' {

return pattern == path

}

return len(path) >= n && path[0:n] == pattern //HERE

}Workaround

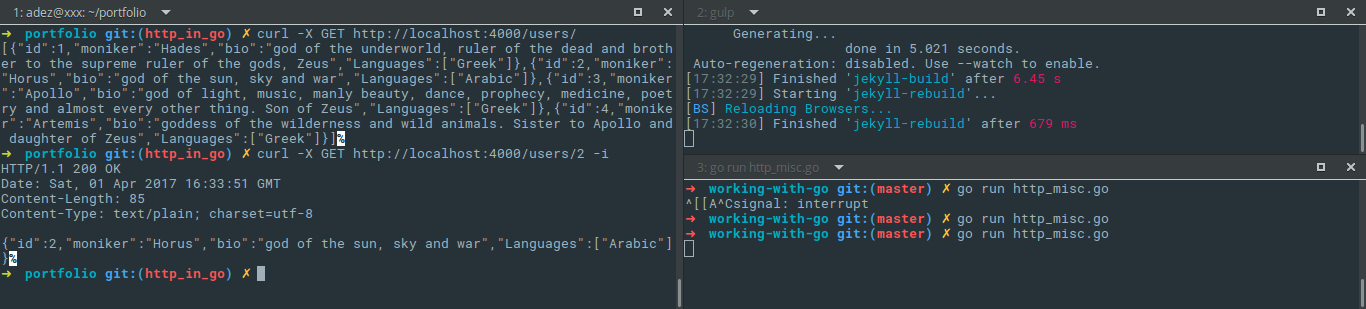

To fix this, we would have to manually inspect the request path, get the id - users/2 .

If an id exists in the path, we check if we have a god with the id. If yes, respond with it's details, else return a 404 HTTP error.

With this checks, we also have to make sure the registered path users/ still works as expected.

type users struct {

}

func (u users) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

s := r.URL.Path[len("/users/"):]

if s != "" {

id, _ := strconv.Atoi(s)

var requestedUser *user

var found bool

for _, v := range allUsers {

if v.ID == id {

found = true //god exists

requestedUser = v

break

}

}

if found {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

j, _ := json.Marshal(&requestedUser)

fmt.Fprintf(w, string(j))

return

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusNotFound)

return

}

//No id was specified so we return the default

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

j, _ := json.Marshal(allUsers)

fmt.Fprintf(w, string(j))

}

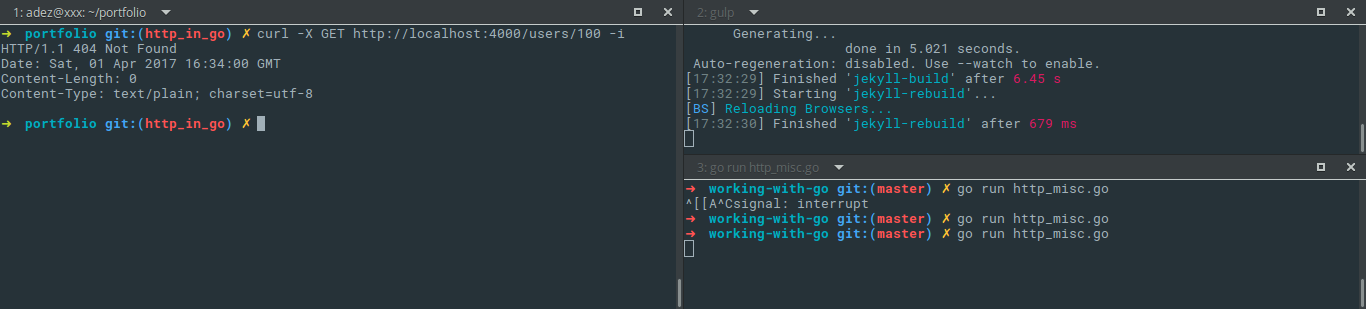

And for the 404 response if a god couldn't be found

While this is a legit fix and would even work in a large app with complex routing requirements, it is just saner to make use of a third party package that integrates this functionality.

The one with a custom Multiplexer

After examining the flaws of the default router it would be in all best interest to make use of a third party package that provides the functionality we need. There are tons of them right now but here are the ones i find most interesting :

pressly/chigorilla/muxgoji

Below is an example of an application that makes use of pressly/chi

package main

import (

"github.com/username/app/handler"

"github.com/goware/jwtauth"

"github.com/pressly/chi"

"github.com/pressly/chi/middleware"

"log"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

router := chi.NewRouter()

router.Use(middleware.RealIP)

router.Use(middleware.Recoverer)

router.Use(middleware.RequestID)

router.Use(middleware.Heartbeat("/pingoflife"))

router.Use(middleware.CloseNotify)

router.Use(middleware.Timeout(time.Second * 60))

router.Group(func(r chi.Router) {

r.Post("/login", handler.PostLogin())

r.Post("/signup/:token", handler.PostSignUp())

//:token => Parameterized route

})

router.Group(func(r chi.Router) {

r.Route("/app", func(ro chi.Router) {

ro.Use(jwtauth.Verifier)

ro.Use(jwtauth.Authenticator)

ro.Route("/collaborator", func(roo chi.Router) {

roo.Post("/create", handler.CreateCollaborator())

roo.Post("/delete", handler.DeleteCollaborator())

})

ro.Route("/posts", func(roo chi.Router) {

roo.Post("/create", handler.CreatePost())

roo.Delete("/:id", handler.DeletePost())

roo.Put("/:id", handler.UnpublishPost())

})

})

})

log.Println("Starting app")

http.ListenAndServe(":3000", router)

}Below is what one of the handler might look like:

package handler

import (

"github.com/pressly/chi/render"

"net/http"

)

func PostLogin() func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

//Plumbering comes here

render.JSON(w,r, ...)

}

}Note that while this is slightly difference in syntax from

func PostLogin(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request). It actually does the same thing. This is just to open the oppurtunity for stuffs like dependency injection (of a DB connection, mailer or whatever have you) in your handlers.

Nothing has changed except for the fact that we create a new router(Handler), attach some routes and tell net/http to make use of our router by http.ListenAndServe(":3000", router).

With the DefaultServeMux implementation, we passed nil to ListenAndServe as the second argument which instructs Go to make use of the default multiplexer.

The main point is if you pass a handler (router) to ListenAndServe, it makes use of that, but if nil is passed, it makes use of DefaultServeMux.

I hope this post helps someone understand how HTTP requests are handled and processed in Go.

In the previous example with

pressly/chi, i made use of middleware. I hope to write about that sometime in the future - just remember that they are still Handlers.Update : Blog post on middleware

Footnotes

<div id="footnotes"> </div>0 This is one of the reasons why i so much love Go. Go is written in Go.

I can decide to take a look at packages i am interested in - for instance net/http - and figure out how stuff works which is even why i could write this post in the first place

1 net/http isn't trying to be the one true multiplexer as that i think would have a drastic effect on the community

as other legitimate and better solutions might be looked down upon since they aren't official.

Update :=> I was wrong as per net/http not being the only true multiplexer, Russ Cox who works on the language has more to say about this here